Bosnia’s liberals are enabling a far-right fascist to get closer to power

This year marks the thirtieth anniversary of the Bosnian Genocide, a series of events catalysed by the stubborn fall of communism in Yugoslavia. The devastation of that period has been somewhat forgotten, as the neoliberal guardians of peace swooped in to pick up the pieces. That insecure ease is stirring again, however, as shown with Bosnia’s recent elections—and it could be argued that this is due to the failures of that very peace process.

The Serbian far-right is mobilising, and one man in particular, Milorad Dodik, is following the same anti-establishment course that other wannabe despots have taken. And 23 November’s election results prove that his allies can hold the fort for him, as Sinisa Karan won a marginal majority.

But he is only able to operate this way and cause this much trouble because the guardians of the state he seeks to dismantle are giving him an easy route to undermine them.

What was done to Yugoslavia

The Srebrenica Massacre is the most famous and potent of the atrocities that were inflicted upon Bosnians and Croats in the early 1990s. But tens of thousands were also murdered, displaced, raped, and permanently traumatised by Serb and Croat militias, with only some of the perpetrators facing prosecution.

A precarious peace was established in Dayton, Ohio, in the autumn of 1995, when the leading figures of each national group met to discuss a plan for the future, which resulted in the equally precarious state of Bosnia-Herzegovina.

The state, divided into two parts, included a majority Croat/Bosnian area, the Federation of Bosnia-Herzegovina, as well as a Serbian statelet, Republika Srpska. The unification was so fraught that an independent overseer from the United Nations was stationed in the country as a persistent peace-negotiator, grandly titled the High Representative for Bosnia-Herzegovina.

The entire arrangement, and this position in particular, has always been controversial, as all groups within the nation frequently voice their concerns about the imposition of an unelected bureaucrat. What unintended consequences could ever have emerged from this arrangement?

The current High Representative is Christian Schmidt, a man whose background is aptly described as prime neoliberal careerism. As a former member of Angela Merkel’s cabinet, he made the move to Bosnia as High Representative for the UN in 2021. Since then, he and Dodik have routinely clashed over the autonomy of Republika Srpska as a region. The High Representative holds the prerogative to annul and approve laws (known as the Bonn Powers), effectively making him an executive authority in the country.

Republika Srpska and its re-emerging fascist front in Bosnia

Dodik isn’t a new face in the politics of Bosnia-Herzegovina—in fact, he’s been around since the late 1980s. A Bosnian Serb, he was born in Banja Luka, the capital of Republika Srpska, and has been a separatist agitator from the beginning of his career, developing a more ethno-nationalist edge in recent years.

An agitator and a brute though he may be, his brash anti-establishment tactics have been very successful, making many uneasy about the future of Bosnia’s politics. His behaviour is especially worrying due to his exceptionally close relationships with the world’s most powerful fascists and autocrats—namely Trump, Putin, and Orban—trenching through the same mud that they have.

In February, he was tried in Sarajevo and given a one-year prison sentence, alongside a six-year ban on holding public office, for ignoring the decision of the High Representative—a serious offence under the Bosnian Constitution. Since then, the Sarajevo court has upheld the verdict despite his appeals, and elections for his replacement took place last night – returning an unsurprising win for another Dodik ally. He has also skipped bail for his prison sentence to fly to and from the Kremlin, while Bosnian police have repeatedly failed to arrest him, despite his extensive collection of “anti-terrorist” bodyguards.

Cast in Teflon

But as with his comrades abroad, Dodik is seemingly cast in Teflon. He can avoid jail for as long as necessary, and the crowd that rallied for him during his trial in Banja Luka will continue to support him, and his puppets now in the Prime Ministry of Republika Srpska will act on his behalf. He can only do this because the state appears both so powerful and yet so illegitimate to those in Republika Srpska. Today’s autocrats feed their movements with the money of the wealthy and the anger of ordinary people at their state and the heavy-handedness of neoliberalism.

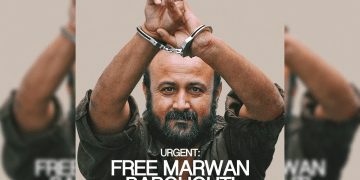

Featured image via the Canary